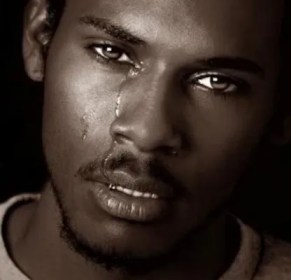

Who Will Cry for Black Boys in a Pseudo-Post-Racial Society? (Revisiting Antwone Fisher)

“Who will cry for the little boy, the boy inside a man / Who will cry for the little boy, who knew well, hurt and pain / Who will cry for the little boy, who died and died again / Who will cry for the little boy, a good boy he tried to be / Who will cry for the little boy, who cries inside of me” (Antwone Fisher)

As you glance into the life of Antwone Fisher one can gain a clearer perspective on his journey to become a stable adult and how he (like many black youth today) had to learn how to cultivated a politics of resilience and perseverance to survive his childhood trauma. Some of fluctuations and fluidities that take place in Antwone’s life can be used to describe how childhood incidents still have implications for black boys growing up in the rigors of the 21st century.

“It don’t matter what you tried to do, you couldn’t destroy me! I’m still standing! I’m still strong! And I will always be!” These were the words that Antwone Fisher spoke as he declared his triumph of all the societal, interpersonal, and childhood barriers that he was forced to overcome. Antwone Fisher became a ward of the state only weeks after he was born. He was placed into foster care and remained there for the majority of his childhood. In the movie, as Fisher grew up he was repeatedly abused (sexually, emotionally, and through physical harm). As the Dr. Jerome Davenport offered Antowne psychiatric treatment in the movie, he attempted to intervene on various stressors. These stressors were rooted in issues from the Antwone’s childhood. As these issues surfaced, one could begin to understand how various traumatic events or “stressors” in a stable persons life can cause a ripple effect that is cross-generational. These are the same stressors that are impacting black boys in inner cities across the nation.

The struggles, understandings, and lessons, which the original Antwone Fisher wrote about in his autobiography. I think that through a strengths based approach (an idea that emphasis agency and power of the individual), an analysis of intersectionality and an examination systemic barriers, one will be able to understand how common stressors in the black community can be overcome.

When entering into the conversation about Antwone’s life and largerly the life of black youth, one must first take into consideration the idea of “intersectionality.” Leslie McCall defines the term as “the relationships among multiple dimensions and modalities of social relationships and subject formations.” Intersectionality seeks to understand how various levels of marginalization impacts communities simultaneously.

Taking strengths based approach Antwone used his past to augment his life and become a successful father, community member, and motivational speaker. When he was a young boy his struggle with inferiority and abandonment had a lasting impact on his life. However, in his adult years he proudly explains how he regained his self-efficacy through revisiting the past, challenging existing systems of power, and understanding that there are always multiple barriers facing black youth simultaneously.

If we want to help black boys, black girls, brown youth, trans youth of color, gay youth of color, disabled youth of color, and the various groups that are experiencing oppression on multiple and various levels, we must all make an effort to recognize those barriers that exists, and make those around us (who don’t have to reflect on barriers that don’t exists in their own lives) start to think about the disadvantages that young people go through. Most importantly, it is crucial to stop beating down black youth with the failures of their past, but encourage them with their own personal strengths and values they hold. When black boys cry, we must use those tears as symbols for what must change in the next generation. Antwone’s story is not to be understood as an occasion to tell black boys about their failure, but as an opportunity for hope and the humility it takes to know that tomorrow can always be better than today.